SigmaQ Corporate Default Risk Technology

The Case of Credit Suisse Part 2

When we published our article on the Credit Suisse case three and a half months ago, we could not have foreseen that the parallels to the 2008/09 financial crisis would further unfold so quickly and with such a dramatic and sad ending for one of the world’s largest and most renowned banks, as we have seen in recent weeks.

It is a bit alarming to witness the financial system’s continued vulnerability to almost the same ingredients that led to the 2008/09 financial crisis. Politically induced (regulation for regional banks was relaxed in the US in 2018) uncontrolled growth of banks, collapsing hedge funds (Archegos) and last but not least a complete failure of the rating agencies whose job it would have been to alert market participants to the looming risks. We are not the first, nor will we be the last, to question the usefulness of these ratings, but here is their track record in relation to recent events:

• Credit Suisse

the three major rating agencies, S&P, Moody’s and Fitch, still assigned an investment grade rating to Credit Suisse on Friday last week, after the company basically collapsed.

• SVB

S&P and Moody’s downgraded SVB from investment grade to junk one day after the collapse.

• FRC

S&P and Moody’s downgraded SVB from investment grade to junk on March 17, a week after the collapse of SVB.

• Signature Bank

S&P and Moody’s downgraded Signature bank to junk status one day after it was closed down by the state.

• Some other banks like PacWest, Zion, UMB Financial, Western Alliance have been put on negative watch, still being investment grade, only last week with the entire sector being in turmoil for several days by then already.

The amount to stabilize the global financial system for the collapse of these banks currently stands at over $500 billion and includes a significant amount of government funds.

But did this crisis come completely out of the blue and simply could not be detected as these downgrades ex-post might imply?

Let us come back to our post from December, where the downward spiral of Credit Suisse was analysed via SigmaQ PD in more detail. In the figure below we provide an updated version of the SigmaQ PD for Credit Suisse.

As we have pointed out in December already, our model shows that Credit Suisse’s credit risk essentially started to rise significantly beginning 2022. And it has not decreased since then; on the contrary, it has increased in fluctuations, reaching new levels each time. This can be compared with the assessment of, for example, Moody’s: Credit Suisse’s credit rating has always been in the investment grade range and very stable over the last two years. It never fell below Baa2. Moody’s EDF (Moody’s measure of a company’s probability of default) for Credit Suisse has remained virtually unchanged over the same period and is at the same level as that of its competitors J.P.Morgan, Citi Bank, Goldman Sachs, etc. .

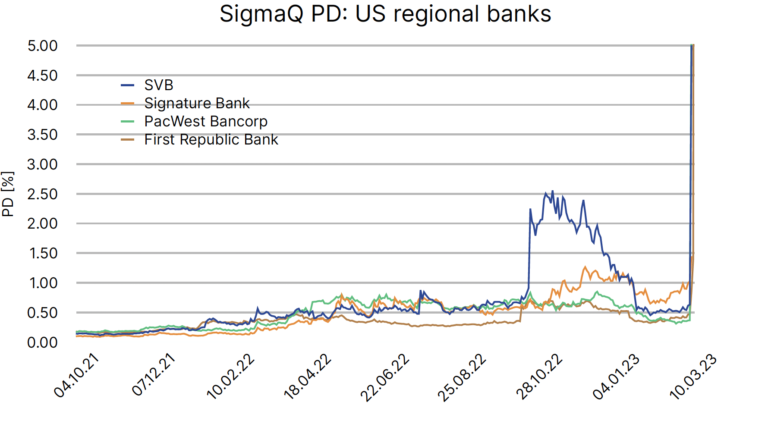

What about the US regional banks then, which are closely connected to the case of Credit Suisse when triggering last weeks turbulences? In the figure below we show the SigmaQ PD for some of these banks.

The PDs of these banks have been increasing more or less monotonically since the beginning of 2002, with the average PD of these companies increasing from about 14 basis points in October 2021 to almost 100 basis points towards the end of 2022, i.e. by almost 700%. Then, in October 2022, we see the first dramatic increase in the PD of SVB. The reason for this is easily found in SVB’s Q3 2022 financial results and the market’s reaction to them: that was the moment it had been recognized that the business model of financing the tech venture capital market had come under pressure and that business-as-usual would become much more difficult. This logic is easy to follow, and our PDs reflect the mechanism behind this decline quite well.

Based on these observations, it is hard to claim that the current crisis came completely out of the blue. Our models are not opinions based on intuition, but the result of cutting edge mathematical models for predicting default probabilities. No subjectivities, no ratings, just observable data, which in our model are a sophisticated combination of a company’s balance sheet data and market dynamics.

However, if a company’s creditworthiness is assessed using rating models that look at these companies in isolation, i.e. without taking into account the immediate market dynamics, they may simply not be able to identify the real risks while variables such as liquidity, assets and liabilities are still in the “green zone”.

When evaluating the creditworthiness of a private company, it is certainly useful to look only at assets and liabilities, the industry in which the company operates, management and some other qualitative aspects. But is that enough when dealing with highly interconnected, publicly traded banks whose financial stability depends in part on the stock price and depositors’ opinion of the bank, which in turn is linked to the stock price? We don’t think so. This approach was developed many decades ago when it may have had merit, but in today’s financial landscape it no longer seems fit for purpose and can produce downright absurd results.

Of course, we are not saying that the failure of rating agencies to properly assess corporate creditworthiness is the cause of the current turmoil. But we do believe that because of the systemic entrenchment of these ratings in financial markets, their failure is helping situations to deteriorate as too many market participants are kept in the dark about the true risks for too long if these credit ratings continue to show clear skies even when the hurricane is already in sight.